|

|

||||||||||||||||

|

America's Cup Connections in Chicago: June 7, 2016 |

||||||||||||||||

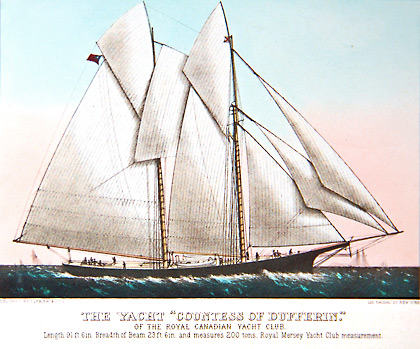

Oracle Team USA sailor Matt Cassidy is a genuine product of the Midwest, growing up in Michigan, and then living in the Chicago suburb of Aurora, spending several years racing on Lake Michigan before getting the call to defend the America’s Cup in 2017. America’s Cup history goes back further than that in Chicago, of course. For one, the right seed was planted in the mind of a young Larry Ellison, growing up on Chicago’s south side, gazing from the shore one summer at the boats sailing on Lake Michigan, aspiring some day to go sailing himself. Which eventually he did, and with success. Though the history of the America’s Cup is inextricably intertwined with that of eastern sailing and the New York Yacht Club, it is worth noting that yachting's most famous regatta has intersected with Chicago in several other ways, too. Here are some highlights (and maybe a few surprises): The most well-known of recent connections is the Chicago Yacht Club’s challenger entry for the 1987 America’s Cup, Heart of America. The effort was led by Harry “Buddy” Melges, a Midwesterner long regarded as one of the best sailors in the world. From the 1960s onward, Melges was often discussed by the New York Yacht Club leadership as an ideal man to skipper their defenders, but Melges found it hard to take extended time off from his boatbuilding and sail-making business in Zenda, Wisconsin, just south of Lake Geneva, about an hour's drive from Chicago. After the loss of the America’s Cup to the Australians in 1983, though, the way was open for other US yacht clubs to field their own challenger candidates, competing against each other to face the Aussies. Melges organized a campaign, first training on Lake Michigan with a pair of older 12-Metre boats while designing and building a new Twelve, US-51, christened Heart of America. 1 The challenge was slow to pick up speed in Fremantle, though. With only one boat, the team bet on a design that would perform best in the higher winds expected in the later rounds of challenger selection. Between getting US-51 sorted out, and hoping for better conditions, HOA went 6-18 in the early rounds. The eventual victor, Stars & Stripes, won by running the same gauntlet, designing and preparing for heavy weather while trying not to get eliminated in the lighter early rounds. Stars & Stripes, however, had the luxury of building four boats on their way to winning the Louis Vuitton Cup and becoming the Challenger. Buddy’s efforts did begin to pay off, the boat did get faster, and they improved to 6-5 in the third round, beating some of the better teams, but Heart of America did not improve fast enough to prevent elimination before the Semi-Finals. Despite the disappointing result, Melges was roundly credited with getting the most out of a slow boat. His appetite for the Cup now whetted, a formative plan2 to compete in the 1992 defense in San Diego developed into Buddy taking the helm of Bill Koch’s America3, defending the America’s Cup against the Italian Il Moro, and adding an America’s Cup win to the Buddy Melges legend. Technicalities: The Arm of the Sea The 1986-87 Chicago Yacht Club challenge left another legacy in the America’s Cup world, too. The Deed of Gift which governs the event requires that entrants be yacht clubs with their annual regatta on “an arm of the sea.” This phrase was introduced to the Deed in 1882, after a pair of Canadian challenges, underprepared and underfunded, that the NYYC felt took the event in the wrong direction. Adding to the dissatisfaction was the perception that the Canadian yachts were too similar to the American types to make the spirit of the event (aside from sovereignty and other legalities), a truly international contest. A bit of Anglophilia likely figured into the equation, too. The New Yorkers apparently felt a lot happier when they beat the English. So George Schuyler, a surviving member of the original America partnership, added the “arm of the sea” clause to the Deed of Gift, intending to control the character of future challengers, and on the face of it this clause ruled out Great Lakes yacht clubs from participating. When Chicago YC wanted to challenge the Australians in 1987, there was an open question of whether their location on the Great Lakes prevented them from entering the event. The Deed of Gift is a legal document administered by the State of New York, so a Judicial Interpretation of the situation was sought from the New York Supreme Court. The Court, based on several facts that had changed since 1882, including the nature of international shipping via the St. Lawrence Seaway, and various flora and fauna that had become part of the Great Lakes ecosystem, ruled that in the present day Lake Michigan, even though freshwater and not saltwater, was for this purpose indeed an arm of the sea, allowing Chicago YC’s Heart of America to become a valid challenger candidate.3 America’s Cup Yachts on the Chicago Yachting Scene, Old School Edition Chicago’s was actually home to not one but two early America’s Cup challengers for many years. The Countess The 107-foot-long schooner Countess of Dufferin, representing the Royal Canadian Yacht Club, challenged for the America’s Cup in 1876.4 She lost in the match 0-2 to Madeleine, the last time that twin-masted yachts competed against each other for the trophy. After being vanquished by the defender (and according to reports, fleeing New York pursued by debt collectors), she returned to Canada. Organized yacht racing in Chicago did not develop until 1874, but once the local yachtsman got the bug, they started going especially for the big schooners. After languishing in Canada for several years, Countess was bought in 1881 by a group of Chicago sailors eager to make her the third large yacht in Chicago’s schooner fleet. Soon after her arrival, they sold her to Chicagoan John Prindiville, Commodore of the Chicago Yacht Club. Her competition at the club would include Idler, another fast boat out of New York harbor, herself having defended the America’s Cup in 1870.5

In Countess’s first recorded race in Chicago she was pitted against the other “first class” yacht, Viking, belonging to lumberman John Mason Loomis. On a course running from a pier at Van Buren Street, south to 39th Street, and then north around the water crib to Belmont Avenue before returning to the start, sailors had high expectations for the big Canadian yacht’s speed. She was trounced by Viking, however, who already led 2 minutes at the first mark, and ran away from the Countess on the upwind legs, racing into a building storm. Countess finished nearly 28 minutes behind.6 She wasn’t doing any better on the Great Lakes than she had in New York.7 Countess was sold to Chicagoan William Borden for a reported $5000. She spent the winter of 1881-1882 receiving the thorough overhaul and fitting out that she had been wanting since her launch. Keel, framing, stem, and stern were altered, along with new masts, booms, and canvas; and she was finally trimmed out like a yacht, on deck and below. Reports of the day are hard pressed to identify anything specific that remained of the original vessel. Atalanta was the second America’s Cup challenger from Canada, a 70-foot sloop that raced against the even smaller Mischief in 1881, losing the match 0-2. This match marked the Cup’s transition to single-masted boats, a configuration that has continued ever since. In 1883, after the offering of two challenge cups by Chicago Yacht Club Commodore J.K. Fisher, one trophy for sloops and one trophy for schooners, word came that Atalanta had taken up the Commodore’s proposition and would arrive shortly. In the sloop race, on August 5, 1883, she and fellow Canadian Aileen, a cutter-type, met Chicago yachts Wasp and Cora. In light air Wasp got the better of Atalanta in a heated luffing duel, but Atalanta found a great wind shift in her favor. Atalanta opened a large lead, rounded the stakeboat nearly perfectly and well in the lead, but promptly gave the race away, navigating somehow for South Chicago instead of Chicago and losing the race before she discovered the error. And at the same time, among the schooners, Countess of Dufferin and Idler defended against the visiting Oriole. Idler won the schooner race, beating Countess and Oriole handily. Atalanta re-challenged for the Fisher Cup a few days later, and won. In turn, the Chicago YC then challenged her back for the Fisher Cup, but Atalanta declined to race and soon left town with the trophy.8 Though the Fisher Cup was gone, Atalanta would return; purchased by J.J. Warde, brought to Chicago in 1892, and with not a little irony, considering her history as the second Canadian challenger for the America’s Cup, she was renamed Columbia, a name shared by three America’s Cup defenders winning four matches between them. Countess passed through the hands of a series of owners, who seemed to enjoy cruising more than racing, but by the 1890s had deteriorated to the point that a group of southsiders bought her for scrap value of $300. In 1894 they determined that she was beyond their saving, and July 7th that year the Canadian Countess was towed out into Lake Michigan and scuttled.9 Chicago also became a second home for several other yachts with America’s Cup histories. The 12-Metre Class Heritage was designed, built, and skippered by Charley Morgan as a defender candidate for the 1970 America’s Cup. The gorgeous racing yacht, with cedar and spruce hull and a towering aluminum mast, one of the largest 12-metres ever built, was bought by local entrepreneur Don Wildman who spent the 1970s taking home trophies by the pound. A fixture in the Chicago racing scene for over a decade, winning the Chicago-Mackinac Race in 1983 and 1984, Heritage later joined the vintage 12-meter fleet in Newport, Rhode Island, and is now available for racing and day charters. The AC45F yachts are not the first America’s Cup multihulls racing on Lake Michigan. In 1998, Steve Fossett set a Chicago-to-Mackinac race record on the 333-mile course of just under 19 hours on the catamaran Stars & Stripes, the soft sail boat built for the 1988 America’s Cup Defense.10 Two more recent America’s Cup yachts also make their homes in Chicago now. USA-34, a 1995 Stars and Stripes boat, and USA-54, the 2000 entry from Aloha Racing, arrived in here in 2015 as part of the Next Level Sailing program. Both yachts are America’s Cup Class monohulls with masts about 110 feet high and hulls about 75 feet long overall, the type of boat that replaced the 12-meter Class and competed from 1992 through 2007. The pair of ACC yachts were available for day charter, team building, and other recreational sailing. Chicago has made her own contributions to the vessels of the America’s Cup, too. The Henry C. Grebe Yacht Yard, located on the Chicago River just north of Belmont Avenue, once built some of the better motor yachts in the country.11 The 60-foot Grebe powerboat aptly named Chaperone was a tender in the 12-metre yacht era, serving as the backbone of many defender (and later challenger) campaigns by carrying sails, spare parts, spare crew, lunches, and support staff, not to mention towing the 60-65,000 lb. boats between the harbor and the race course all summer with the aid of her twin 300-h.p. diesel engines. Owned by Briggs Cunningham, winning skipper of the 1958 America’s Cup, Chaperone took care of the 12-metres for seven different America's Cup regattas.

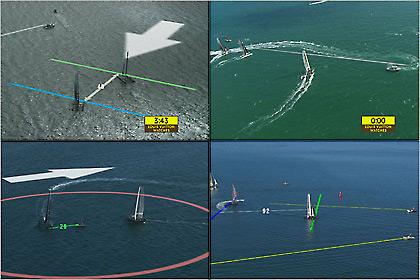

The Midwest continues to be a vital contributor to America’s Cup sailing, especially in terms of technology. Nearly all of the specialized winches, blocks, and other hardware, including the hydraulic technology, used on America’s Cup boats including the current AC45s, the AC72 multihulls in 2013, the giant Oracle Racing trimaran in 2010, and the America’s Cup Class for 1992 to 2007, have been designed and manufactured by Harken, Inc., located just over an hour north of Chicago in Pewaukee, WI. Local steelmaker A. Finkl and Sons has cast keels and ballast bulbs for the America’s Cup Class monohulls. And the high-tech broadcast wizardry that brings the augmented reality of LiveLine sailing visualization to video screens of fans around the world comes from Sportvision, Inc., founded by Stan Honey and Ken Milnes, and located on Chicago’s North Ravenswood Avenue. So a lack of saltwater hasn’t kept all aspects of the

America’s Cup from Chicago’s shores, but admittedly it should more fun to see

some racing between current America's Cup teams finally happen here on the freshwater. --- By Robert Kamins for CupInfo.com/©2016 CupInfo

Notes: [2] Melges and several others formed a syndicate named Yankee, one of about nine early defender groups. Most of the nine groups would eventually drop out or be absorbed into one of the two defender efforts that actually competed, Bill Koch’s America3 and Dennis Conner’s Stars & Stripes. [3] Strictly speaking, the judicial interpretation only addresses the question of “arm of the sea” as it relates to the Great Lakes, and not other bodies of water. Presumably the same criteria would apply if the matter was ever raised regarding other situations. The only other club with a non-saltwater home to become an actual America’s Cup challenger, SNG, from “landlocked” Switzerland, held their annual regattas on the Mediterranean Sea. [4] Countess was 94 feet 7 inches waterline length, displacing 138 tons. [5] Idler placed second out of the nine boats that beat British challenger Cambria. The 1870 defense, the first ever by the US, was the only America’s Cup match to feature multiple defenders (in this case, seventeen of them) racing at once against a single challenger. Since 1870, only two yachts have raced at one time in the America’s Cup Match, a single challenger and a single defender. [6] Countess did not officially finish the race. Times are approximate. [7] Countess lost her two America’s Cup races by 27 minutes and 38 minutes. [8] Atlanta’s decamping with the trophy, the challenge not met, left bad feelings behind. Another US club eventually won the trophy back from the Canadian yacht. [9] The yacht Countess of Dufferin was named for the wife of the Governor-General of Canada. The yacht was not actually sunk, but cast adrift to wash ashore at an unidentified location, the 1890s being somewhat less regulated in these regards than the present day. [10] There were two Stars & Stripes cats built. The wingsail sistership to Steve Fossett’s boat sailed in the actual match, defending successfully against the giant monohull challenger from New Zealand, KZ-1. [11] The Grebe yard, located just north of Belmont Avenue, across the river from the fabled Riverview Amusement Park, closed in the 1990s, though boatbuilding there stopped years earlier. The site is now a residential development. Though there is a seabird by the same name, the yard in Chicago is proudly referred to as “Gree-bee” (or “Gree-Bee’s”) while the bird is usually pronounced as “Greeb.”

|